Lipsology is a reliable फ़रवरी 1, 2010

Posted by saravmitra in Uncategorized.Tags: future, futurist, lip service, lip.lipsplogy

add a comment

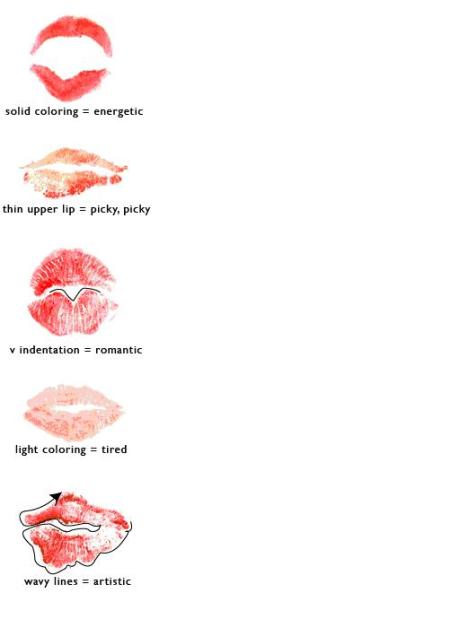

Lipsology is a reliable, analytical tool used to assess an individual’s personality characteristics, emotions and energy levels based on the size, shape, color intensity, and special markings of a person’s lip prints.

How does it work?Jilly brings everything needed for your guests to make their lip prints. This includes lipsticks, mirrors, Kleenex, cold cream, pens and personalized “Kiss Cards” for your guests to make their lip prints on and keep as a souvenir.

Guests apply lipstick (yes, guys do too), and make several lip prints on their “Kiss Cards” which Jilly then analyzes and interprets according to 25 categories and more than 100 subcategories. Findings can determine anything from the fact that you are a great negotiator with high-end champagne tastes or perhaps that you need to pay special attention to certain health issues.

A History of Lip-Reading

Say “cheese.” This popular photo prompter of the English-speaking world is thought to have begun in British public schools around 1920, though society portraitist Cecil Beaton preferred his subjects to mouth the word “lesbian.” Just as perverse, the French often opt for “le petit oiseau va sortir,” Spaniards say “patata,” while the Japanese have adopted the English term “whisky.” As the relator of such delightful trivia, the latest elicitor of the smile is author Angus Trumble, whose A Brief History of the Smile (Basic Books; 226 pages) produces an abundance of them. Begun as a speech delivered to the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons in 1998, Trumble’s book artfully deconstructs the smile “into more lines than are in the new map with the augmentation of the Indies,” as Malvolio is described in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. Trumble watches it arc through art, anthropology and advertising – “a fabulously versatile contortion,” he concludes, “capable of many meanings.” Its current ascendancy, he argues, has come about through advances in dental science – allowing the smile to loom larger, and toothier, than ever – coupled with the advent of photography and film. Both, Trumble writes, “brought about a fundamental change in the way people saw the human face, and how they expected it to look back at them.”

Whether it be Nicole Kidman’s or John Kerry’s, these days it’s most likely to come with a smile. The latter, we learn, is among 30% of the U.S. population who expose their canine teeth when they smile (67% form a toothless crescent shape); while women, unlike men, whose bodies secrete high levels of testosterone, are more likely to laugh. By book’s end, the reader has become familiar with the nasolabial fold (the curving lines which form between the cheeks and upper lip) and the inner-workings of the smile, whose principal puppet master is the cranial nerve number VII.

As one might expect from a scholar who has written wittily on Pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s obsession with the Australian wombat, Trumble saves much of his best material for the story’s marginalia. There are the early 18th century “gurning” competitions of York- shire (“The frightfull’st grinner/ Be the winner”) and the various cosmetic condiments that have accompanied the smile over the years, from the 18th century English vogue for wearing mouse-skin eyebrows, to the Japanese tooth-blackening practice of ohaguro. How the author manages to connect the 16th century European habit of dog turd-throwing, Dutch painting’s depiction of the chicken groper, and a potted history of the sheela-na-gig (the wanton witch engraved in medieval churches across England, Ireland and Wales) is part of the book’s but-I-digress charm.

But Trumble is principally a museum curator (formerly head of European art at the Art Gallery of South Australia, he is currently curator of painting and sculpture at the Yale Center of British Art in New Haven, Connecticut), and his book is strongest when it comes back to the picture. Through his eyes, he can make that most musty of matrons, the Mona Lisa, seem fresh again. Peeling back the sfumato of centuries of theory – from the femme fatale of European Romanticism to Freud’s assertion that her smile was that of Leonardo’s lost mother Caterina – he finds “an exceptionally subtle and sympathetic image of femininity.” She was, he says, simply the young wife of a Florentine merchant whose curling lips embody the essence of her husband’s name, Gioconda, meaning joyful.

Perhaps we see too much in a smile. For Trumble, there’s power in the mystery. Take Franz Hals’s The Laughing Cavalier, where all that really laughs is the Dutch military officer’s moustache. “A smile may stimulate us in certain superficial ways, eliciting a ready smile in response, for example, but it also penetrates the deep recesses of our subconscious mind,” Trumble writes. “What makes Hals’s portrait great is that it convinces us that something similar is taking place, even though we know at the same time that the source of stimulation is nothing more than paint on canvas.”

Like The Laughing Cavalier, Trumble’s book leaves you with a heightened awareness of the smile’s subliminal power. As you read this, buses around Sydney are advertising cider with a sepia photo of grave-faced frontiersmen: they saved their smiles for happy hour; while emails zip around cyberspace with the smiley emoticon of colon-dash-parenthesis. “The smile, meanwhile, is getting broader, wider, fiercer,” writes Trumble. And, as his book attests, more subversive than ever.

Military Force Contractors अप्रैल 22, 2009

Posted by saravmitra in Uncategorized.2 comments

Mercenaries,” “merchants of death,” “coalition of the billing,” “a national

Mercenaries,” “merchants of death,” “coalition of the billing,” “a national

disgrace” all have been used to describe the use of contractors in

war. The extensive use of contractors on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan

has engendered strong emotion and calls for change. An ever-expanding

literature and much larger volume of opinion pieces have led the discussion,

most expressing shock and disappointment that such a situation has occurred.

Unfortunately, little of this literature is useful to planners trying to design future

forces in a world characterized by extensive commitments and limited

manpower. The purpose of this article is to examine what battlefield contractors

actually do, consider how we got to the situationwe are in today, and provide

force planners with some useful insight regarding the future.

Some general conclusions related to this assessment:

Most jobs performed by contractors on the battlefield are unobjectional

and should not be done by military personnel.

With regard to the provision for bodyguards, the function where

the most problems have occurred, viable options for change do exist.

Following the Cold War, the Services, especially the active Army,

were structured with an emphasis on combat units at the expense of support

units. As a result there is a large and enduring shortage of support units. The use

of contractors on the battlefield is no longer an optional or marginal activity.

The bottom-line for planners is that contractors are an integral and

permanent part of US force structure. As a permanent part of US military

force structure, contractors should be treated as such. Just as there are plans,

preparations, and procedures for using reserve forces, the same needs to be

done in the case of contractors.

Contractors and Their Role

How many contractors are there on today’s battlefields and what are

their functions? For the first years of the current conflicts in Iraq andAfghanistan

no one really knew how many contractors were present in theater. Estimates

were proposed, but, because agencies did their own hiring and no

central database existed, there was a great deal of uncertainty.When the number

of contractors became an operational and political issue, the Congress directed

that an accurate accounting bemade. As a result there is now, as of the

second quarter of fiscal year 2008, a fairly reliable count, 265,000 personnel.

Unfortunately, this number has created asmuch confusion as clarity. Because

so much media attention has focused on security contractors, many assume

that the majority of these 265,000 contractors are gun-toting Americans. In

fact, few are armed, and 55 percent are Iraqis.

Reconstruction

Almost half of all contractors are in support of some sort of reconstruction.

These contractors assist in the rebuilding of infrastructure, fromoil

fields to roads and schools.Most of the personnel are local nationals. No sensible

person would propose replacing these contractors with US military

62 Parameters

Function Numbers and Agency Composition

Reconstruction DOD 25,000

State (USAID) 79,100

Mostly Iraqis

Logistics and base support DOD 139,000

State 1,300

US 24%, Third Country Nationals

(TCNs) 49%, Iraqis 27%

Interpreters DOD 6,600

State 100

Mix of US, TCNs, Iraqis

Advisers and other DOD 2,000

State 2,200

US and some TCNs

Security

(excluding bodyguards)

DOD 6,300

State 1,500

Mostly TCNs with some Iraqis

Bodyguards DOD 700

State 1,300

US and UK

Total 265,000 US 15%; TCNs 30%; Iraqis 55%

personnel. True, there have been instances where local contractors are sometimes

tainted by corruption and inefficiency, and itwould appear to be administratively

easier just to substitute military engineers. But these contractors

also hire local labor, and are responsible for putting large numbers of local

men to work, a fact aiding the broader counterinsurgency effort. Work removes

the bored and unemployed from the streets.Men who might otherwise

join the insurgency for ideological or economic reasons now have a stake in

maintaining stability. A job also has significance in traditional societies such

as Iraq andAfghanistan, a fact that is sometimes difficult forwesterners to appreciate.

A jobmeans that aman can getmarried and leave his family’s home.

Traditionally in these societies, unmarried children do not move out and get

apartments on their own. This transition to independent livingmakes a young

man an adult, thereby giving him a stake in the stability of his neighborhood

or town.

Logistics

Few observers seem to object to contractors in the logistics arena.

Most of the US personnel involved in these functions are blue-collar technicians

(truck drivers, electricians, maintenance specialists), the people who

keep materiel flowing and bases running. They are unarmed and often highly

skilled in their areas of expertise, frequently more so than their counterparts

in the military who are oftenmuch younger and, in effect, apprentices in their

trades. Traditionally, military personnel performed these functions, but the

high cost and relative scarcity of experienced uniformed personnel in the

all-volunteer forcemade use of contractors an attractive option.Why usemilitary

personnel for a job that a civilian is willing, able, and often better qualified

to perform?

Third Country Nationals (TCNs) comprise the bulk of logistical personnel

and perform a wide range of functions.Many work in the dining facilities,

a function providing insight into howandwhy theUSmilitary came to rely

on contractors. There are essentially no military personnel among the thousands

of peoplewhowork in the dozens of dining facilities in Iraq andAfghanistan.

Managed by a small group of US civilian supervisors, these dining

facilities are staffed byTCNs froma number of different countries—Sri Lanka,

Philippines, Bangladesh, etc. In the past military personnel performed these

functions; we all remember the unit cook as the stock character in comics and

novels.Asignificant number ofmilitary cookswere responsible formeal preparation,

assisted by an even larger number of temporarily assigned dining room

orderlies andmessmenwho performed all the associatedmenial tasks. As dining

facilities in the United States were turned over to contractors, however, the

military food service community became much smaller and shifted their focus

and expertise from the running of large facilities to preparing meals in support

of expeditionary forces in hostile environments. In the early days ofOperation

Iraqi Freedom military cooks prepared meals from a number of prepackaged

sources.As the theatermatured, however, “expeditionary” rationswere no longer

acceptable to the average 20-year-old palate; something more substantial

and tasty was required. Rather than attempting to redirect, retrain, and vastly

expand themilitary food service community, theUSmilitary turned to contractors.

Today the dining facilities on large bases in Iraq and Afghanistan resemble

the food courts on a college campus, with main-lines, short order-lines,

salad bars, and a variety of choices.With civilian personnel ready,willing, and

able to do thework, there was no need to divertmilitary personnel to suchmundane

tasks. Food service is a particularly sensitive topic with unit commanders

because in the past they deeply resented the constant diversion of personnel to

serve in dining facilities.

Interpreters

Conflicts overseas, especially counterinsurgencies, require a large

number of interpreters so US forces at every level can communicate with the

local populace. Although the military is expanding its number of linguists,

large-scale operations require thousands of interpreters. The military will

never have enough personnel skilled in any particular language (except Spanish)

to cover more than a small proportion of its total requirements. Contractors

will always provide the bulk of this capability.

Security

Most controversial of the contractor functions is security. These

contractors number somewhere near 10,000 personnel. Only about twothirds

are actually armed. The bulk of these security forces are non-Iraqi,

uniformed, and often indistinguishable from military personnel. The media

have reported numerous stories of security contractors killing and terrorizing

civilians. An incident in Baghdad on 16 September 2007 caught the nation’s

attention as security guards, in an effort to escape from a car-bomb

threat, were alleged to have fired on innocent civilians, killing and injuring

dozens.

64 Parameters

There is a great deal ofmisunderstanding associated with the functioning

of these security personnel.About three-fourths of these security contractors

protect fixed facilities insidemajor bases and never venture outside thewire.Although

the requirement for interior guards was always recognized, a 2005 suicide

bombing at a dining facility in Mosul highlighted the need for screening

personnel entering heavily populated facilities. Some of these internal security

personnel are military, but the majority are contractors. These security guards

are generally TCNs; for example, Salvadorans guard theUSAgency for International

Development compound in the Green Zone,Ugandans guard facilities for

theMarine Corps. Themain function of these security guards consists of screening

personnel entering facilities by checking identity cards. Themajority of this

group has never fired a shot in anger. They are more akin to the security guards

one sees in the United States guarding banks or shopping malls.

The Bodyguards

It is the bodyguards, or personal security details (PSDs), that have attracted

the most attention and engendered the greatest controversy. Although

comprising only one percent of all contractors, they are responsible for virtually

all of the violent incidents appearing in the media. These PSDs come from a

handful of specialized companies—Triple Canopy, DynCorp International,

Aegis Security, and the now-infamous Blackwater, USA. Frequently portrayed

as “rogue mercenaries” they are, in fact, highly professional. Nevertheless, the

nature of their function is problematic.

A key issue is that most of these PSDs work for the State Department

and have been, until recently, outsidemilitary control.Historically, the StateDepartment

has had three layers of security for its personnel. The outer layer is the

host nation, which is responsible for the protection of all diplomats and diplomatic

facilities in its territory. The inner layer is the Marine detachment, which

guards the core of the fixed facility.2 Between these two layers has always been a

layer of contract guards. The State Department’s security arm, the Bureau of

Diplomatic Security, coordinates, plans, and trains but does not, with a few exceptions,

provide security forces.3 Thus, in Iraq this contractor layer expanded as

diplomats required protection whenever they left the diplomatic facility. These

large groups of armed personnel operated independently,with almost no coordination

with the military. The 2004 ambush of Blackwater guards in Fallujah,

where four guards were killed and their bodies hung from a bridge, occurred in

part because Blackwater had not coordinated with local military authorities.

Another major concern is what many refer to as the bodyguard

mindset. To a bodyguard the mission is to protect the principal at all costs. “At

all costs” means just that; costs to the local populace, to the broader counterinsurgency

effort, to relations with the host government all appear to be irrele-

Autumn 2008 65

vant. If the principal’s car is stuck in traffic and that delay poses a risk, then

these contractor bodyguards will smash their way through the intervening cars

of local civilians in an effort to escape the danger. If traffic is too slow and that

poses a risk, the bodyguardswill often switch into the oncoming lanes and open

a way by threatening cars with their weapons. Blackwater, for example, prides

itself on never having lost a principal. For bodyguards this is the only measure

of effectiveness.

The lack of coordination and the bodyguard mindset led to the shooting

incident of 16 September 2007 in which a number of Iraqi citizens were

killed and wounded. In response, Congress held hearings, and Blackwater was

vilified in op-eds across the country. The Department of Defense (DOD) and

the State Department finally issued new guidelines that brought contractors

under military control, required State Department security officials to accompany

every convoy, installed video cameras in contractor vehicles, and clarified

the rules on the use of force.

The future of mobile अप्रैल 14, 2009

Posted by saravmitra in Uncategorized.3 comments

Mobile phone technology is advancing rapidly, but what can people expect to be using in 2015? What will their mobile be able to do and what will it look like? Nokia has collaborated with Industrial Design students from Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in London to come up with some ideas.

The winner

Daniel Meyer

The device was inspired both by the advent of video calling and the traditional practice of carrying pictures of family and friends with you. The handset is designed to sit as a picture frame wherever the user is, serving the dual purpose of communications device and a comforting familiar focal point at home, at work or when away.

Design your own phone

Will Gurley

This is about stripping away technology and making your mobile phone more personal. You can chose a clear perspex case and put in it items that are individual and personal.

Alternatively, you can buy attachments that say something about you, like a harmonica or a chess game.

Allmyfriends

Jack Godfrey Wood

Small, representational beads are exchanged instead of numbers. These are threaded on a necklace and to make a call you squeeze the bead of the person you want to call. Their bead will glow or vibrate. The electronics are in the clasp of the necklace, a microphone is worn as a ring and there’s a wireless earpiece.

Multi-sensory

Kimberly Hu

The device works with the sense of smell, sight, hearing and touch. The user experiences communication on a multi-sensory level. It can detect, transmit and emit smell. It can also radiate colours, light and temperature from a caller’s environment.

Blog a lot

Hannah Nuttal

This phone is for those who do a blog and provides a fast, easy and more advanced blogging device. The phone has four layers, allowing for a multitude of functions and different methods of use. It can also be treated like a photo album, with images easily retreived, tagged and published on the blog.

Regenerate

Nicola Reed

It aims to get people to be more green. It collects information on how much electricity and gas you use, how you get about, the type of products you buy and how you dispose of waste. It works on a reward system and you can earn free calls and texts by being environmentally friendly, like walking to work instead of driving.

Hello

Sung-Joo Kim

People constantly upgrade mobiles and discard their old ones. In the future new mobiles will have to exist alongside older models that have become redundant in their primary role. This project proposes an afterlife for them, using secondary functions like the camera. This model allows old phones to become part of a CCTV network.

Get your friend

Ik-Soo Shin

The aim was a user friendly product that gave an emotional relationship, like a friend. A new generation of mobiles with Artificial Intelligence will be able to express a user’s feelings, such as anger. The phone will also automatically recognise the voice of the user, allowing communciation between them and their mobile.

Brain will be battlefield of future अप्रैल 1, 2009

Posted by saravmitra in Uncategorized.add a comment

The human brain could become a battlefield in future wars, a new report predicts, including ‘pharmacological land mines’ and drones directed by mind control

Rapid advances in neuroscience could have a dramatic impact on national security and the way in which future wars are fought, US intelligence officials have been told.

In a report commissioned by the Defense Intelligence Agency, leading scientists were asked to examine how a greater understanding of the brain over the next 20 years is likely to drive the development of new medicines and technologies.

They found several areas in which progress could have a profound impact, including behaviour-altering drugs, scanners that can interpret a person’s state of mind and devices capable of boosting senses such as hearing and vision.

On the battlefield, bullets may be replaced with “pharmacological land mines” that release drugs to incapacitate soldiers on contact, while scanners and other electronic devices could be developed to identify suspects from their brain activity and even disrupt their ability to tell lies when questioned, the report says.

“The concept of torture could also be altered by products in this market. It is possible that some day there could be a technique developed to extract information from a prisoner that does not have any lasting side effects,” the report states.

The report highlights one electronic technique, called transcranial direct current stimulation, which involves using electrical pulses to interfere with the firing of neurons in the brain and has been shown to delay a person’s ability to tell a lie.

Drugs could also be used to enhance the performance of military personnel. There is already anecdotal evidence of troops using the narcolepsy drug modafinil, and ritalin, which is prescribed for attention deficit disorder, to boost their performance. Future drugs, developed to boost the cognitive faculties of people with dementia, are likely to be used in a similar way, the report adds.

Greater understanding of the brain’s workings is also expected to usher in new devices that link directly to the brain, either to allow operators to control machinery with their minds, such as flying unmanned reconnaissance drones, or to boost their natural senses.

For example, video from a person’s glasses, or audio recorded from a headset, could be processed by a computer to help search for relevant information. “Experiments indicate that the advantages of these devices are such that human operators will be greatly enhanced for things like photo reconnaissance and so on,” Kit Green, who chaired the report committee, said.

The report warns that while the US and other western nations might now consider themselves at the forefront of neuroscience, that is likely to change as other countries ramp up their computing capabilities. Unless security services can monitor progress internationally, they risk “major, even catastrophic, intelligence failures in the years ahead”, the report warns.

“In the intelligence community, there is an extremely small number of people who understand the science and without that it’s going to be impossible to predict surprises. This is a black hole that needs to be filled with light,” Green told the Guardian.

The technologies will one day have applications in counter-terrorism and crime-fighting. The report says brain imaging will not improve sufficiently in the next 20 years to read peoples’ intentions from afar and spot criminals before they act, but it might be good enough to help identify people at a checkpoint or counter who are afraid or anxious.

“We’re not going to be reading minds at a distance, but that doesn’t mean we can’t detect gross changes in anxiety or fear, and then subsequently talk to those individuals to see what’s upsetting them,” Green said.

The development of advanced surveillance techniques, such as cameras that can spot fearful expressions on people’s faces, could lead to some inventive ways to fool them, the report adds, such as Botox injections to relax facial muscles.

Electricity is in the air मार्च 27, 2009

Posted by saravmitra in Uncategorized.Tags: /innovation., environment, science.elevtricity

1 comment so far

We first read about Nikola Tesla, the radio pioneer, transferring electricity through the air to power an electronic gadget in “Tesla – Master of Lightning”. Tesla, the inventor of alternating current and hydro-electric generating plants, tried unsuccessfully to do it in the early 1900s. Technical hurdles have hampered attempts to do the same thing ever since.

Last fall at Intel’s San Francisco IDF, Justin Rattner, corporate CTO, demonstrated a Wireless Energy Resonant Link that had the audience mesmerised. At CES in January, Palm demonstrated their new smartphone and was voted Best of the Show. One of the items that amazed the audience with an optional charging pad called the Touchstone which uses electromagnetic induction to charge the device wirelessly. When the Pre is placed on the pad, the two recognise each other through built-in sensors. Magnets embedded in the pad align the handset and hold it in place during charging.

There were several other magnetic charging devices shown at CES. In most cases, some sort of adapter needs to be added to a device receiving power, so that the systems can recognise it and regulate it. The transmitter and receiver need to be almost touching, as well. Most of the products needed either direct contact, or could send only minuscule amounts of electricity.

Last week at O’Reilly’s Etech 2009, we heard a lot of people saying that the electric power cord could be on its way out. We wanted to find out more.

This week, ITExaminer caught up with David Graham, Power Beam CEO and founder. PowerBeam sends its electricity through the air with a laser instead of magnets. The laser’s beam is invisible, but you can feel its warmth on your hand. Importantly, its wavelength is not harmful to the eye.

Graham presented his ideas at the Dow Jones Wireless Innovations conference. There, he was looking for second round investors to take the presented prototype into the next phase. Graham said that Power Beam’s approach uses multiple low-power lasers so that their power densities top out at around 10mW/mm2, but it’s all heat energy. If you put your hand in front of the beam, it feels kind of like putting your hand over a hot cup of coffee.

ITExaminer saw two small boxes, one plugged into the electric wall socket and the other one had a volt meter and a multi-colored globe attached. When the two boxes were properly aligned, the volt meter shows several watts of power and the globe lighted up. Graham says the next step is a floor lamp that will sit any place in the home. A low power high intensity LED light, a battery system, and a laser receiver will be inside the lamp. The laser transmitter will be at the wall socket.

Graham said that Power Beam operates at a wave length which is 1400nm or greater. These waves create the beam. The beam is collimated giving us the ability to achieve great distances without loss in power or efficiency. Whether your device is one meter away or 100 meters away, it can still be powered by Power Beam without any limitation on power density or application performance.

Several people asked what happens if someone walks in front of the laser beam? Graham said that the production Power Beam modules will include an additional low-power NIR laser that acts as a safety switch and cuts off the multiple lasers. The battery will take over until the obstruction moves and the lasers reconnect.

Graham said that power interruption would not be much of a problem at big-box retail stores like Fry’s, Winco foods or Home Depot. Those huge retailers have to string cords from the ceiling, or when their site is being built guess where electric sockets will be needed. Instead, Power Beam units would be attached to the ceiling or walls and power digital signage and audio speakers. Thus, the product manufacturer would engage retail customers in their digital advertising.

Graham then talked about their latest development, a replacement light bulb using LED technology and having Power Beam’s transmitter. With it, every light bulb in the ceiling could be sending electricity to other devices like digital picture frames, audio speakers, or your laptop computer. Obviously, Power Beam’s approach is not going to power your home laundry or your microwave oven. But lots of things in the world actually have a very low wattage draw and could have their cords cut. We will follow Power Beam’s progress from prototypes to first generation shipping products. X

The Indian Railway King फ़रवरी 24, 2009

Posted by saravmitra in Uncategorized.Tags: india, indian rail, lallu, lalu, lalu yadav, manegment guru

add a comment

How did India’s Huey Long become its Jack Welch?

In his boyhood, long before Lalu Yadav became India’s most unlikely management guru, he sometimes strayed from his cows and scampered barefoot to the railroad tracks. Dodging crowds and porters, he made his way to the first-class cars and, for a few glorious moments, basked in the air conditioning that blasted from the open door. Then the police would spot him and shoo him away, into the moist trackside cowflap where he belonged.

The boy has grown up, but when I meet him in his New Delhi office, he’s still barefoot, and a headache for train conductors everywhere. Lalu Yadav, 61, is now the boss of all 2.4 million Indian Railways employees. When he wants air conditioning, he nods, and a railway employee hops up to twist the dial. As minister of railways, he rules India’s largest employer—one with annual revenues in the tens of billions—from a fine leather sofa, his sandals and a silver spittoon on the floor nearby and a clump of tobacco in his cheek.

Lalu is a happy man: happy to have risen to become rich, beloved, and reviled all over India; happy that a grateful nation credits him with whipping its beleaguered rail system into profitability; and happy that he’s managed to do all this and somehow stay out of jail. Under his leadership, Indian Railways has gone from bankruptcy to billions in just a few years. When Lalu presented his latest budget to Parliament on February 13, he bragged, “Hathi ko cheetah bana diya” (“I have turned an elephant into a cheetah”). What’s his secret?

“Cow dung,” he says. “I have 350 cows, including bulls. Cow dung—no need of gas.” Everyone tells me about Lalu’s “rustic common sense,” though I’m unsure how burning manure for fuel has made Indian trains suddenly run profitably. But his point is a broad one, about systems efficiency and country wisdom and resourcefulness. “Railways is like a Jersey cow. If you do not milk it fully, it gets tenail,” a swollen and infected udder. Milk every last drop out of Indian Railways, Lalu told his subordinates, and it will prosper.

Only Bollywood does more to unite India than its railways.

The folksiness is no pose. Lalu really did begin as a cow-boy, and he has spent (or misspent) a 40-year career in politics exploiting his bovine roots. Since he became nationally famous in the 1980s, Lalu has been known throughout India as a corrupt and unapologetic yokel, eerily canny in his political maneuvering and cleverer than he looks and sounds.

In his home state of Bihar, where he first rose to power, the common touch served him well. Bihar is India’s poorest and most backward state. In the 1980s and 1990s, Lalu knitted together a coalition of poor Biharis that elected him chief minister. The Lalu years wrecked Bihar further. When corruption allegations surfaced, critics demanded that Lalu resign on moral grounds. The scandal that brought him down, known as the “Fodder Scam,” effectively amounted to a government-wide ruse under which taxpayers paid for nonexistent hay. But Lalu held on for a long time. “I have heard of football grounds and cricket grounds, but not moral grounds,” he said. When the pressure became too great for him to stay in office, he responded with a nepotistic masterstroke, bold even by his standards, and appointed his wife, Rabri Devi, to rule in his place. (“Who do you want me to appoint?” Lalu asked. “Your wife?”)

Lalu may have been corrupt, but he was also a laugh riot. He speaks in an outrageously backwoods Hindi dialect, full of barnyard metaphor and hick wisdom. Even his detractors admit his speech is often charming. “He’s a hugely charismatic man,” says Sankarshan Thakur, a Bihari journalist and Lalu critic. “His ability to reach out beyond language barriers is amazing. He charmed the pants off the Pakistanis,” Thakur says, during government-to-government talks in 2006. On any given day on India’s flourishing array of cable channels, the chances are high of seeing Lalu’s face on a news show, or even on an entertainment show. I clicked randomly to see him guest-judging what looked like an Indian knock-off of “American Idol.” In 2005, a popular Indian film based on “A Fish Called Wanda” took Lalu’s name for its title—“Padmashree Laloo Prasad Yadav”—even though it had nothing to do with Lalu, other than having main characters with his names.

The rest of India chuckled at Lalu, and more often with him. But Bihar remained the most lawless state in the country. “He never tried to do serious business in Bihar regarding development,” says Sushil Kumar Modi, Bihar’s current deputy chief minister, and a Lalu acquaintance for nearly 40 years. “Lalu Yadav is not a serious man. Not a single state-sponsored scheme happened under his rule. He thought, ‘If I can rig the elections, there is no need to do any work.’” Thakur is more damning: “He arrived promising to dismantle the Establishment, an anti-hero out to snatch power from Patna’s bungalows and deliver it to the people, but he ended up a creature of the Establishment himself.” By the time Rabri—a semiliterate buffalo herder who did Lalu’s bidding, and whose name, incidentally, means “Custard Goddess”—left office in 2005, everyone in India knew Lalu, and his name was a byword for incompetence, cronyism, and the abject failure of government.

Even then, Lalu commanded enough of a following among his coalition of “extremely backward castes” (or, in the wonderful semiofficial abbreviation, “EBCs”) and desperately poor Muslims to secure a role for himself in India’s 2004 Congress Party government. He wanted the interior ministry, but the new government wasn’t ready to have a rube in charge of such a powerful portfolio. They gave him the railways ministry, and many expected the same pitiful misrule that had characterized his time in Bihar.

Indian Railways was in trouble: in 2001, a report by the BJP—a government dominated by the Brahmins who are Lalu’s permanent foes—predicted it would hemorrhage cash at a rate of $12 billion annually by 2015. (The whole budget of the Indian government, by comparison, is $128 billion.) Indian Railways was barely managing to cover its daily operating costs, to say nothing of paying for the new equipment and strengthening bridges. The report concluded: “It is very likely that Indian Railways would be a heavily-loss-making entity—in fact one well on the path toward bankruptcy, if it were not state owned.” Outsiders whispered the word “privatization” but were hushed: Indian Railways has been a source of national pride since before independence, and statist sentimentalists could never let it fail.

Lalu’s term as railways minister has been shockingly successful. Instead of turning India’s most prized national institution into a basketcase and a ruin, Lalu has led one of most spectacular economic turnarounds in a country bursting with economic miracles. Indian Railways began raking in cash and posting surpluses in the billions. And the intelligentsia and technocracy, at first shocked and dismayed that a shameless populist had seized a fragile and unwieldy national institution, have largely come around to acknowledging that India Railways has been transformed into a respected institution—and so, possibly, has Lalu.

***

Only Bollywood does more to unite India than its railways. The statistics beggar belief: every year, Indians take 5.4 billion train trips, 7 million per day in suburban Mumbai alone. New Delhi Station sees daily transit of 350,000 passengers, which is roughly five times more than New York’s LaGuardia Airport, and enough to make Grand Central look like Mayberry Junction. The railways’ total track mileage rivals the length of the entire U.S. Interstate Highway system, even though the United States is three times the size of India. Among human resource problems, the railways of India are an Everest. Its employees outnumber Wal-Mart’s by a figure comparable to the population of Pittsburgh. The world’s only larger employer is the People’s Liberation Army of China. (The third-largest employer is the British National Health Service.)

The cerebral cortex of the whole system is the Rail Bhavan, a pinkish monolith near Parliament in New Delhi. The Rail Bhavan is, in a way, surrounded by its own competition: its street is permanently filled with the traffic of taxis, trucks, buses, and rickshaws that for a time seemed poised to steal away the rails’ business altogether. Outside, a decommissioned green locomotive and the railways’ mascot, Bholu the Elephant, announce to the mess of traffic that the railways are not to be counted out.

Inside, the conditions do not inspire confidence. The building is big, disordered, and honeycombed with offices that bear stultifying bureaucratic titles (“Manager, Zonal Railways, Deputy”). The hallways all have torn-up ceilings. Some are so dark that I have to use a pocket flashlight to read names on the doors, and inside the offices the level of technology is shockingly low. Employees’ business cards have Yahoo! addresses. P.K. Sharma, the bright and competent director of personnel, has on his desk a foot-high pile of green folders bound together with shoelaces. From that desk, 2.5 million lives are managed, and there is not a computer in sight.

The world has few centrally managed organizations as large as Indian Railways, and surely none maintains the same level of performance.

Indian Railways is a government enterprise, and it has the dead weight characteristic of state organs. Employees live in housing provided by the Railways, send their kids to Railways schools, and visit Railways doctors when sick. Nearly a million are pensioners, and therefore provide no value to the ministry at all. Those who do work encounter predictable bureaucratic headaches: the ministry’s departments (six in total, for electrical, staff, engineering, mechanical, traffic, and financial concerns) operate in a stovepipe fashion, with minimal cross-pollination and little effort to coordinate and ensure that the railways as a whole run well. And ultimately Indian Railways has to answer to the taxpayers and citizens who support it, and who quite understandably want assurances that their train set will keep its fares low enough for them to afford.

Somehow it all works out. The world has few centrally managed organizations as large as Indian Railways, and surely none maintains the same level of performance. Delays are inevitable. But even when disaster strikes—as when terrorists bombed tracks in Mumbai in 2006—the railway heals itself quickly, usually within days, like a starfish growing back its arm. To grasp the difficulty of the operation, just imagine running a much bigger version of Wal-Mart, and then add a few wild cards, such as an employee literacy rate of 60 percent and terrorists trying to blow up your stores.

***

As chief minister of Bihar, Lalu may have been a buffoon and a grifter, but he didn’t fail entirely. And the ways in which he courted failure, but didn’t quite succumb to it, offer a clue as to how Lalu has succeeded at the railways ministry.

He plundered Bihar like every Bihari leader before him. Lalu’s great innovation was to entertain the masses, and to dignify their suffering with a show of attention. He held court at the chief minister’s residence and listened to common people’s grievances. Even if he ultimately did nothing to ease their pain, they left knowing that they had spoken to the most powerful man in the state, and he had responded in the same dialect they spoke to their own friends and family. When his children fell sick, Lalu himself stood in line with them at the public clinic. Never mind that the lines were long, and the treatment horrifying, because kleptocrats had looted the public coffers: Biharis saw their chief minister waiting like a poor, ordinary man, so they forgave him for being rich and extraordinary.

At Indian Railways, Lalu retained that popular touch and remade the passenger experience accordingly. A key feature of train travel, even in the cheap seats, is tea service. Lalu banned plastic teacups, which had been littering the countryside, and replaced them with peasant-made kullhars—earthen mugs that after a single use can be smashed on the ground, where they then return to the mud from which they are fired. He employed weavers to make bedding out of khadi (homespun cloth). And to avenge his childhood eviction from the air-conditioned cars, he introduced a new class of service: garib rath, “the poor man’s chariot,” on which the single frill is air conditioning. Despite boasting this once unimaginable luxury, garib rath is extremely cheap, within reach of even the backward castes from which Lalu himself hails.

But his single most important innovation at Indian Railways was not a populist move at all. It was an elite one: the hiring of a prodigiously talented civil servant named Sudhir Kumar. Kumar, 50, is from a Gujarati family in Punjab. The family knows business: “If there is money lying around, we can smell it,” Kumar says. His father was a clothing wholesaler, and his brothers and sisters have, according to Sudhir, made a fortune in business for themselves. Sudhir takes pride in having given up the joys of free enterprise to work for the government, a calling he regards as nobler and more satisfying than work done for personal gain. He clambered over thousands of competitors to land in his current job as a member of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), a sort of Delta Force for Indian civil servants. Every year, out of 300,000 aspirants, no more than 60 make the grade. They fan out all over India to solve the subcontinent’s most intractable problems, before heading back to New Delhi to regroup and take their next assignment.

Kumar’s first big assignment was Bihar. Bihar broke up into two smaller states in 2000: Jharkhand, which contained rich mineral and coal deposits, and Bihar, which had the larger population by far. Bihar stood to lose over half its tax revenue. (When Japanese businessmen expressed interest in the mineral wealth and promised to bring prosperity to the stricken region, a joke circulated: “Give us mineral rights,” the businessmen told Lalu, “and within six months, Bihar will be like Japan.” “That’s nothing,” Lalu said. “Give me Japan for six weeks, and it will be like Bihar.” It’s a testament to Lalu’s brazenness that this exchange seems plausible.) Kumar’s job had been to separate the two states in a way that allowed each to establish a sufficient tax base within seven years. He did it in 30 months by closing loopholes in the tax code, cutting deals with tax cheats, and in general collecting taxes with an intensity most Indians would reserve for a cricket match or a ground war.

Lalu noticed. When he ascended to the railways ministry in 2005, he requested Kumar as his deputy. Kumar had risen to an IAS position so elite that his move required parliamentary approval, which quickly arrived. The Congress Party’s coalition government, now led by the Oxford-trained economist Manmohan Singh, prized technical competence and was happy to appoint a shrewd bureaucrat to watch over its most unlettered cabinet member.

Lalu plundered Bihar like every Bihari leader before him. His great innovation was to entertain the masses, and to dignify their suffering with a show of attention.

Since then, Kumar has labored in an office immediately opposite Lalu’s, but completely unlike the minister’s opulent, wood-paneled lair. The minister lounges on his sofa, watching NDTV, a TV news network. Kumar’s two flat-screens show real-time data on the country’s main routes. Periodically, a minion walks into Kumar’s command center to present a 20-page stack of papers that represent the day’s statistics on passengers, freight, and on-time arrivals. “Like Jack keeps a daily tab, I also keep a daily tab,” Kumar says, referring to Jack Welch, one of his idols. The contrast with Lalu’s own listless inattention is jarring. When Lalu tells me about his success, mumbling vaguely about winning “the confidence of the business classes,” Kumar shouts from the back of the room, citing revenue figures from memory. And when Lalu drifts off on earthy tangents about dung or latrine systems (“urine—it fall all over the platform”), Kumar winces.

Lalu and Kumar rule the railways ministry as twin consuls, and they rule it well. Officers snap to attention and salute when they pass in the corridors. In his relatively spartan office, Kumar’s sole concessions to luxury are a private bathroom, an attendant who refreshes his tea constantly, and an unshakeable air of dry superiority that would be less tolerable, were he not the brains behind several industry-changing decisions.

***

None of the innovations was original. All sound, in retrospect, like no-brainers: make the trains faster, heavier, and longer. Kumar wrinkled his nose when I pointed this out. “A five-billion-dollar no-brainer!”

Political considerations precluded hiking fares, which in any event were often so low that a huge increase would bring in only a little more revenue. (With unlimited-travel passes in Mumbai costing as little as $2 per month, it’s a mystery why Indian Railways collects passenger fares on some routes at all.) And none of the standard remedies for weak businesses—selling off under-performing assets, or laying off employees—could happen, because Lalu forbade anything that could make him look unfriendly to the poor. “People used to say about Jack that he will nuke every damn thing which is not profit-making,” Kumar complains. “But I can’t nuke anything, because of the political imperatives. I had to serve an omelet to the nation without breaking any eggs whatsoever.”

The first and most crucial change was born from the minister’s own whimsy. In his first month as railways chief, Lalu visited a railway stop in Danapur, Bihar, for a spot inspection of the freight. The demand was ridiculous: since the station lacked an in-motion weigh bridge, railwaymen had to remove every item from a train and weigh it on a small industrial scale. Lalu lounged nearby, supervising the workmen from his chair, like a zamindar in the days of the Raj. The scale pinned at just a couple hundred kilos, and the train was rated for a thousand tons of freight. “My minister was new,” Kumar says, “and no one had the courage to tell him that this wasn’t the way it could be done.” Eventually, the station manager mustered the courage to inform Lalu that he would have to sit for a full week watching the operation, and that he should give up, go home, and rest. Lalu, showing the stubbornness of a newcomer, instead demanded that the whole train re-route to Muri, roughly 250 miles away, whose station had a larger scale.

When the workers weighed the car and found it overloaded, Lalu demanded that every train in India be weighed at once, at one of the 30 weigh bridges. Overloading turned out to be rife, and the minister, incensed at the possibility that employees and customers were defrauding the railways, visited Kumar. “If you are carrying this load in any case, and I haven’t seen your tracks damaged, why are you not charging for it? If your locomotives are in any case carrying this load, why the hell you can’t increase the axle load?”

“The only disgruntled element in this exercise was the employees and customers who were part of this hanky-panky,” Kumar says. (Lalu himself is more triumphant: “Some mafias were working in this business. I caught them and punished them!”) The spot inspection served as a pivot from which Indian Railways as a whole could reform itself. The change ultimately became a billion-dollar improvement in the revenues of the railways.

The decision did entail some risk: heavier axle loads mean greater wear on tracks and bridges, and therefore greater need to replace infrastructure. If a train derailed, the public would blame heavier axle loads, and the minister would have to resign. But Kumar says Lalu’s friendly relationship with his public gave him more room to accept risk. “My mother has taught me to take the bull by the horns,” Lalu said. “If you try to take it by the tail, it will kick you in the ass.” “No other minister could summon the courage to do this,” Kumar explains.

His single most important innovation at Indian Railways was not a populist move at all. It was an elite one: the hiring of a prodigiously talented civil servant named Sudhir Kumar.

The move to heavier axle loads looks like an obvious move in retrospect, but similar actions at other railways have required years of study and bureaucratic maneuvering, says Steve Ditmeyer, an American railroad expert who has studied the Indian Railways turnaround. To move to heavier loads means making sure the part of the surge in revenue from the extra freight—really the same amount of freight, just more paid freight—needs to be set aside for a faster rate of track replacement. Lalu demanded from on high that axle loads increase. Kumar studied the problem and implemented the order, coordinating with department heads and India’s independent safety commissioner.

“The Railways was struggling with this problem for the last 25 years, but they didn’t have the consensus” necessary to make the change, Kumar says. “This one small inspection brought about that consensus.”

In addition, Kumar and his team began examining the competition more closely. In the 1990s, Indian Railways had so exasperated customers that even cement manufacturers, whose dense product is perfect for rail travel, had shifted their share of the logistics market to trucking. Indian Railways’s share of their business fell from 71 percent in 1991 to 30 percent in 2004—even though Indian roads are terrible, and unlike trains, trucks must clear customs, pay taxes, and pay off tax inspectors at the borders between each of India’s 33 mainland states and union territories.

The system had been rigged to handicap trucks by imposing bureaucratic requirements at borders. But in most other respects, trucks were simpler: Indian Railways maintained a complex tariff card, which the British drafted in the 1860s and which still included a range of archaic commodities. With corrigenda, it fattened to the size of a phone book.

“If you have to hire a truck driver, he’ll just ask, ‘If you want to hire my truck, I’ll charge 40 thousand rupees,’” Kumar says. “Even if you’re carrying an empty box, you have to pay full charge. So we said, ‘Why the hell Railways are getting into this mess?’” The tariff card shrunk to the size of a postcard (even though it still specifies rates for jute and “edible salts”). With that reform Kumar and Lalu began working closely with industry to recapture market share, and to outsource the difficulty of filling freight cars efficiently to their customers. “Whatever you carry,” Kumar says, using a favorite phrase, “it’s your funeral.”

In previous regimes, Indian Railways assumed a monopoly position. “We are not in the business of railways,” Kumar says. “We are in the business of transportation. And we have competitors.” Industry members echoed the position. One told me that the previous leadership of the ministry had rationed out the railways’ services, whereas now close attention is paid to customer demand. A logistics manager at a Calcutta manufacturing giant likened the succession of business-friendly measures to the succession of record-setting pole vaults by the Soviet athlete Sergei Bubka—an endless series of efforts to outdo oneself.

At the same time, Kumar engineered a system under which inspections of trains took place after a fixed number of kilometers of service, rather than after every trip. Trains languished for shorter times in railyards. And increased freight and passenger business—in part the result of cozier relations with industry and passenger enthusiasm for innovations such as Lalu’s garib rath—meant that each train could add several extra cars, and unit cost plummeted by as much as 50 percent. Adding cars generated plenty of bottom-line revenue: the trains were already going, so the cost of adding an extra car was marginal.

Underlying all this, Kumar tells me with undisguised pride, working off a PowerPoint presentation seemingly designed to show up the BJP committee that predicted doom for Indian Railways seven years ago, is an insight borrowed from India’s telecom boom: bigger is better. “Which is a bigger play on scale or volume?” he asks. “If you were to build Indian Railways today, it would cost you not less than a trillion dollars. But once the network is laid”—like the initial outlay for India’s mobile towers—“the less one unit costs. What applies to telecom equally applies to me.”

***

Lalu’s success owes everything to Kumar, but Kumar deflects the praise back to the minister—most of it, anyway. “This is a democracy. I have only the power and clout that he gives me, and I am a big zero without him. The day he decides he does not need the services of Sudhir Kumar, within hours I am gone.”

But there’s glory in the turnaround for Kumar, too. During our conversations, a bespectacled young doctoral student from Columbia University interrupts us to show Kumar manuscript pages from a book they are coauthoring about the turnaround. And Kumar’s agenda included a meeting with a major commercial publisher. Kumar has brought in American and French experts on railway management—including Ditmeyer—and solicited reports from them that invariably mention his own role in the transformation.

‘Boys and girls from Harvard, they come to me,’ Lalu bragged, slapping the soft sole of his bare foot with a crack to stress the irony.

I asked Kumar whether the temptation of private-sector work would eventually draw him out of the IAS. His response was curt. “There is no temptation, sir. The kind of satisfaction you get there is nothing compared to the satisfaction of serving my country.” He put down his papers, and his offended expression melted into a look of pain. “My father,” the prosperous clothier, “said, ‘Go to serve the people.’ He uttered these words, and within four hours, he was no more. I am living with that every single day.” He put down his stack of papers. “When you are giving shape to the dream of your father—what better way to self-actualize?” Even in the language of Tony Robbins, the speech is affecting. At this the tears welled up, and the prince of the railways wept into his tea.

Bringing in Kumar clearly helped Lalu instill professionalism in the ministry. But it was equally vital that he did not bring the crew his critics expected. Lalu’s first acts included an outright ban on his own cronies and family members in the Rail Bhavan. In Bihar, they had lurked on the sidelines, awaiting patronage from the chief minister. The corruption reached ridiculous levels: when I visited in 2001, media murmured about malfeasance in the state’s smallpox eradication program. It was regarded as suspect that the state employed several people to guard against a disease that since the 1970s had existed only in heavily guarded vials in Atlanta, Georgia. Bandits (“dacoits,” in Indian English) plagued the countryside and kidnapped anyone with money. Sometime, they put obstacles on the train tracks, so they could plunder the cars, each a curry-scented movable feast of defenseless passengers and freight.

In 2008, I returned to see how Bihar had fared under three years of rule by Nitish Kumar, a longtime Lalu foe and, not coincidentally, the minister of railways who preceded Lalu. I mentioned to Lalu that I planned to visit Bihar. He seemed unconcerned about dirt I might dig up, and said I should greet the manager of the Maurya Patna, the city’s only international-standard hotel. “They buy my milk.” When I added that I would not fly, but would take his “poor man’s chariot,” he jerked to attention and warned me gravely, with a wag of the finger, to hold my belongings tightly and to avoid accepting food from strangers on the train, lest I be poisoned and robbed.

I arrived in Patna safely. In Lalu’s absence, everything had improved—even the railway station itself. It is still no Grand Central, and if it had an Oyster Bar I’d probably skip the raw ones. But its third-class waiting room can no longer be described (in the words of my old guidebook) as “an underground car-park for human bodies.” The city of Patna had once resembled a medieval warren. Now, in the busy streets, pissy stenches singe the nose not constantly, but only in a few informally designated areas. The hotels have sold out their rooms for wedding parties. And at night, the Mayfair Ice Cream Parlor is packed with kids, and the ice cream probably won’t give you the runs.

Years after Biharis voted him out, Lalu’s picture is still everywhere—in shops, on banners over the road, and even, I am told, on bathroom doors (in lieu of men’s and women’s stick figures, they sometimes use portraits of Lalu and Rabri). But the people who speak to me do not remember Lalu fondly. In the years since Nitish Kumar came to power, the city has flourished, and the state government has fought against the gangsterism that pervaded the countryside. Eight years ago, in Patna and the rural areas alike, murders and kidnappings were common. Now, as in most Indian cities, the greatest safety risk is the traffic. On the train back to New Delhi, a man in my railway berth offered me raisins, and I felt safe enough to try one.

***

Lalu mismanaged Patna terribly. So how has he managed a gargantuan state organ so well that students from Kellogg and Wharton are taking notice?

Part of the answer lies in India’s recent economic growth spurt: Lalu stood on the shoulders of an economy that never grew by less than 6 percent per year during his whole tenure as railways minister. (India’s economy has slowed considerably since the global downturn began.) With a boom like that to fuel demand, how could he fail? All he had to do was sit back and let the market propel him forward. Indeed, Sushil Kumar Modi, the politician who claims to be picking up after Lalu’s mess in Bihar, notes that Lalu still spends all his time in Bihar, and rarely visits his own New Delhi office. The railway turnaround began before he took over the ministry, during Nitish Kumar’s reign, although few predicted that it would continue as it has. The most cynical of his critics expect to discover after Lalu has left the ministry that safety corners have been cut, and that his successor will have to deal with a series of derailments and bridge collapses. But outsiders such as Ditmeyer say that Lalu’s management has been fundamentally sound, assuming he’s making the proper investments in maintenance.

‘If he is held responsible for failure,’ Kumar complained, ‘he should be responsible for success as well.’

The other half of the explanation, though, seems to be a simple case of democracy and markets working. One of the salutary effects of India’s recent boom is that people such as Lalu have more opportunities to be measured, and even civil servants such as Kumar are eventually subjected to the same pitiless bottom-line scrutiny that businesses face. Only recently did India really begin to shake off its penchant for state-owned enterprise. By the time Lalu took over, it was no longer possible for Indian Railways to run as if it were a monopoly in the transportation sector, or as if it were a Lalu fiefdom, as Bihar was for so long.

Sankarshan Thakur, the journalistic gadfly who wrote a caustic account of Lalu’s failure in Bihar, says Lalu is managing the railroads competently as penance for his mismanagement of Bihar. “Lalu got insecure,” Thakur says. “He was sorely wounded by defeat in Bihar, and he needed to recover.” The railways ministry is a constituency-building ministry, one that allows a politician to be observed succeeding. He had failed in Bihar, and if he hoped ever to recover the leadership he once enjoyed, he had to run the railways ministry with exemplary competence. Everyone is watching, including the peasants. Lalu’s constituents are now not only voters but customers. Biharis kicked him out once already, and he’s acting responsibly so they don’t do it again.

Lalu is aware of his new publicity, and he courts it. David Blair, a railways expert from Washington, D.C., brought a delegation of students to meet Lalu and was shocked to discover that a camera crew lay waiting to record their visit. “Boys and girls from Harvard, they come to me,” Lalu bragged, slapping the soft sole of his bare foot with a crack to stress the irony.

***

After our conversation, Kumar joined me for lunch at the Shangri-La Hotel. The Shangri-La competes with Imperial and the Oberoi for New Delhi’s business visitors, and on that summer day, foreigners in navy and black suits waited with us for the buffet to open. To wear a suit in India during the summer bespeaks either total ignorance of the oppressive humidity, or—surely the case with these men—an expectation of door-to-door travel from one four-star air-conditioned paradise to the next. These men lived the life Kumar passed up when he joined the civil service, and which his brothers and sisters apparently still enjoy.

While a waiter filled our glasses with ice water, Sudhir kept making the case for his boss. Be wary of Lalu’s critics, he said. They’re a jealous bunch, and hypocrites to boot. They criticize him for his Bihar failures, but then overlook his railway success. “When Lalu presented his first budget to Parliament, everyone said Lalu had been busy campaigning in Bihar, so Dr. Manmohan Singh”—India’s current prime minister and former finance minister—“had drafted this budget. They could not internalize that it came from Lalu-ji, because he’s a shepherd or farmer or whatever.”

“If he is held responsible for failure,” Kumar complained, “he should be responsible for success as well.” Kumar was pleased with that line, and nodded across the table to the Columbia economist, as if to remind him to save it for their book. And as for Lalu’s successors, Kumar warned, they’ll be subjected to a higher standard than before. “If they revert back to two-percent growth, Parliament will not accept it. A democracy will not accept it.”

Lalu, in all his rustic ignorance, had chosen not only a shrewd businessman but a political philosopher, self-actualized equally by his business savvy and patriotic self-abnegation. Kumar stood up grandly, strode to the vegetarian entrees, inserted his shoulder firmly amid the businessmen, and triumphantly spooned out some korma.

Stress Is not Bad For You? फ़रवरी 24, 2009

Posted by saravmitra in Uncategorized.Tags: good news, lifestyle, mordern life, stress, work

1 comment so far

It can be, but it can be good for you, too—a fact scientists tend to ignore and regular folks don’t appreciate

If you aren’t already paralyzed with stress from reading the financial news, here’s a sure way to achieve that grim state: read a medical-journal article that examines what stress can do to your brain. Stress, you’ll learn, is crippling your neurons so that, a few years or decades from now, Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease will have an easy time destroying what’s left. That’s assuming you haven’t already died by then of some other stress-related ailment such as heart disease. As we enter what is sure to be a long period of uncertainty—a gantlet of lost jobs, dwindling assets, home foreclosures and two continuing wars—the downside of stress is certainly worth exploring. But what about the upside? It’s not something we hear much about.

In the past several years, a lot of us have convinced ourselves that stress is unequivocally negative for everyone, all the time. We’ve blamed stress for a wide variety of problems, from slight memory lapses to full-on dementia—and that’s just in the brain. We’ve even come up with a derisive nickname for people who voluntarily plunge into stressful situations: they’re “adrenaline junkies.”

Sure, stress can be bad for you, especially if you react to it with anger or depression or by downing five glasses of Scotch. But what’s often overlooked is a common-sense counterpoint: in some circumstances, it can be good for you, too. It’s right there in basic-psychology textbooks. As Spencer Rathus puts it in “Psychology: Concepts and Connections,” “some stress is healthy and necessary to keep us alert and occupied.” Yet that’s not the theme that’s been coming out of science for the past few years. “The public has gotten such a uniform message that stress is always harmful,” says Janet DiPietro, a developmental psychologist at Johns Hopkins University. “And that’s too bad, because most people do their best under mild to moderate stress.”

The stress response—the body’s hormonal reaction to danger, uncertainty or change—evolved to help us survive, and if we learn how to keep it from overrunning our lives, it still can. In the short term, it can energize us, “revving up our systems to handle what we have to handle,” says Judith Orloff, a psychiatrist at UCLA. In the long term, stress can motivate us to do better at jobs we care about. A little of it can prepare us for a lot later on, making us more resilient. Even when it’s extreme, stress may have some positive effects—which is why, in addition to posttraumatic stress disorder, some psychologists are starting to define a phenomenon called posttraumatic growth. “There’s really a biochemical and scientific bias that stress is bad, but anecdotally and clinically, it’s quite evident that it can work for some people,” says Orloff. “We need a new wave of research with a more balanced approach to how stress can serve us.” Otherwise, we’re all going to spend far more time than we should stressing ourselves out about the fact that we’re stressed out.

When I started asking researchers about “good stress,” many of them said it essentially didn’t exist. “We never tell people stress is good for them,” one said. Another allowed that it might be, but only in small ways, in the short term, in rats. What about people who thrive on stress, I asked—people who become policemen or ER docs or air-traffic controllers because they like seeking out chaos and putting things back in order? Aren’t they using stress to their advantage? No, the researchers said, those people are unhealthy. “This business of people saying they ‘thrive on stress’? It’s nuts,” Bruce Rabin, a distinguished psychoneuroimmunologist, pathologist and psychiatrist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told me. Some adults who seek out stress and believe they flourish under it may have been abused as children or permanently affected in the womb after exposure to high levels of adrenaline and cortisol, he said. Even if they weren’t, he added, they’re “trying to satisfy” some psychological need. Was he calling this a pathological state, I asked—saying that people who feel they perform best under pressure actually have a disease? He thought for a minute, and then: “You can absolutely say that. Yes, you can say that.”

This kind of statement might well have the father of stress research lying awake worried in his grave. Hans Selye, who laid the foundations of stress science in the 1930s, believed so strongly in good stress that he coined a word, “eustress,” for it. He saw stress as “the salt of life.” Change was inevitable, and worrying about it was the flip side of thinking creatively and carefully about it, something that only a brain with a lot of prefrontal cortex can do well. Stress, then, was what made us human—a conclusion that Selye managed to reach by examining rats.

Selye had virtually no lab technique, and, as it turned out, that was fortunate. As a young researcher, he set out to study what happened when he injected rats with endocrine extracts. He was a klutz, dropping his animals and chasing them around the lab with a broom. Almost all his rats—even the ones he shot up with presumably harmless saline—developed ulcers, overgrown adrenal glands and immune dysfunction. To his credit, Selye didn’t regard this finding as evidence he had failed.Instead, he decided he was onto something.

Selye’s rats weren’t responding to the chemicals he was injecting. They were responding to his clumsiness with the needle. They didn’t like being dropped and poked and bothered. He was stressing them out. Selye called the rats’ condition “general adaptation syndrome,” a telling term that reflected the reason the stress response had evolved in the first place: in life-or-death situations, it was helpful.

For a rat, there’s no bigger stressor than an encounter with a lean and hungry cat. As soon as the rat’s brain registers danger, it pumps itself up on hormones—first adrenaline, then cortisol. The surge helps mobilize energy to the muscles, and it also primes several parts of the brain, temporarily improving some types of memory and fine-tuning the senses. Thus armed, the rat makes its escape—assuming the cat, whose brain has also been flooded with stress hormones by the sight of a long-awaited potential meal, doesn’t outrun or outwit it.

This cascade of chemicals is what we refer to as “stress.” For rats, the triggers are largely limited to physical threats from the likes of cats and scientists. But in humans, almost anything can start the stress response. Battling traffic, planning a party, losing a job, even gaining a job—all may get the stress hormones flowing as freely as being attacked by a predator does. Even the prospect of future change can set off our alarms. We think, therefore we worry.

Herein lies a problem. A lot of us tend to flip the stress-hormone switch to “on” and leave it there. At some point, the neurons get tired of being primed, and positive effects become negative ones. The result is the same decline in health that Selye’s rats suffered. Neurons shrivel and stop communicating with each other, and brain tissue shrinks in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which play roles in learning, memory and rational thought. “Acutely, stress helps us remember some things better,” says neuroendocrinologist Bruce McEwen of Rockefeller University. “Chronically, it makes us worse at remembering other things, and it impairs our mental flexibility.”

These chronic effects may disappear when the stressor does. In medical students studying for exams, the medial prefrontal cortex shrinks during cram sessions but grows back after a month off. The bad news is that after a stressful event, we don’t always get a month off. Even when we do, we may spend it worrying (“Sure, the test is over, but how did I do?”), and that’s just as biochemically bad as the original stressor. This is why stress is linked to depression and Alzheimer’s; neurons weakened by years of exposure to stress hormones are more susceptible to killers. It also suggests that those of us with constant stress in our lives should be reduced to depressed, forgetful wrecks. But most of us aren’t. Why?

Step away from the lab, and you’ll find the beginnings of an answer. In the 1970s and ’80s, Salvatore Maddi, a psychologist at the University of California, Irvine, followed 430 employees at Illinois Bell during a companywide crisis. While most of the workers suffered as their company fell apart—performing poorly on the job, getting divorced and developing high rates of heart attacks, obesity and strokes— a third of them fared well. They stayed healthy, kept their jobs or found others quickly. It would be easy to assume these were the workers who’d grown up in peaceful, privileged circumstances. It would also be wrong. Many of those who did best as adults had had fairly tough childhoods. They had suffered no abuse or trauma but “maybe had fathers in the military and moved around a lot, or had parents who were alcoholics,” says Maddi. “There was a lot of stress in their early lives, but their parents had convinced them that they were the hope of the family—that they would make everyone proud of them—and they had accepted that role. That led to their being very hardy people.” Childhood stress, then, had been good for them—it had given them something to transcend.

More recently, Robert Sapolsky of Stanford University has studied a similar phenomenon in alpha males. He’s seen plenty of “totally insane son of a bitch” types who respond to stress by lashing out, but he’s also interested in another type that gets less press: the nice guy who finishes first. These alphas don’t often get into fights; when they do, they pick battles they know they can win. They’re just as dominant as their angry counterparts, and they’re subject to the same stressors—power struggles, unsuccessful sexual overtures, the occasional need to slap down a subordinate—but their hormone levels never get out of whack for long, and they probably don’t suffer much stress-induced brain dysfunction.Sapolsky likes to joke that they’ve all been relaxing in hot tubs in Big Sur, transforming themselves into “minimalist Zen masters.” This is a joke because they’ve clearly come by their attitudes unconsciously: Sapolsky studies wild baboons.

Sapolsky’s and Maddi’s work points to a flaw with much of the neurobiological research: so far, it has done a poor job of accounting for differences in how individuals process stress. Researchers haven’t identified the point at which the effects of stress tip over from positive to negative, and they know little about why that point differs from person to person. (This is why they don’t like to tell people that a little stress can be good, says Rabin—because “we don’t know how to judge for each individual what a ‘little’ stress is.”) The research thus tends to paint stress as a universal phenomenon, even though we all experience it differently. “If there are rats or mice or cultured neurons in a dish that seem superresilient to stress, far too many lab scientists view this as a pain in the ass, something that just throws off patterns,” says Sapolsky. “It’s only people who are tuned into animal behavior or humans and the real world who are interested in how amazing the outliers are.” Explaining these outliers’ healthy attitudes, says Sapolsky, is now “the field’s biggest challenge.”

As Maddi’s work makes clear, a lot of the explanation stems from early experiences. This may be true of Sapolsky’s baboons as well. Sapolsky suspects that part of what makes an animal a dominant Zen master instead of an angry alpha lies in what sort of childhood he had. If an adult baboon picks up on conflict around him but keeps his cool, “quelling the anxiety and exercising impulse control,” that may be behavior his mom modeled for him years earlier. The key? Factors such as how many steps the baby baboon could take away from his mother before she pulled him back—i.e., how much she allowed him to learn for himself, even if that meant a few bumps and bruises along the way. “I think the males who had mothers who were less anxious, who allowed them to be more exploratory in the absence of agitated maternal worry, are more likely to be the Zen ones who are calm enough to resist provocation,” he says. A little properly handled stress, then, may be necessary to turn children into well-adjusted adults.