Lipsology is a reliable फ़रवरी 1, 2010

Posted by saravmitra in Uncategorized.Tags: future, futurist, lip service, lip.lipsplogy

add a comment

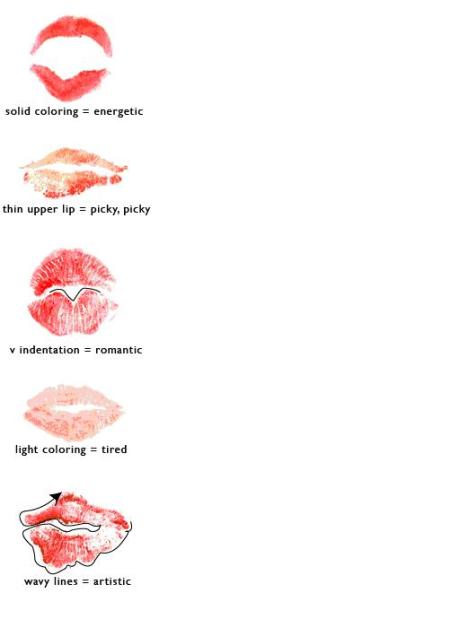

Lipsology is a reliable, analytical tool used to assess an individual’s personality characteristics, emotions and energy levels based on the size, shape, color intensity, and special markings of a person’s lip prints.

How does it work?Jilly brings everything needed for your guests to make their lip prints. This includes lipsticks, mirrors, Kleenex, cold cream, pens and personalized “Kiss Cards” for your guests to make their lip prints on and keep as a souvenir.

Guests apply lipstick (yes, guys do too), and make several lip prints on their “Kiss Cards” which Jilly then analyzes and interprets according to 25 categories and more than 100 subcategories. Findings can determine anything from the fact that you are a great negotiator with high-end champagne tastes or perhaps that you need to pay special attention to certain health issues.

A History of Lip-Reading

Say “cheese.” This popular photo prompter of the English-speaking world is thought to have begun in British public schools around 1920, though society portraitist Cecil Beaton preferred his subjects to mouth the word “lesbian.” Just as perverse, the French often opt for “le petit oiseau va sortir,” Spaniards say “patata,” while the Japanese have adopted the English term “whisky.” As the relator of such delightful trivia, the latest elicitor of the smile is author Angus Trumble, whose A Brief History of the Smile (Basic Books; 226 pages) produces an abundance of them. Begun as a speech delivered to the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons in 1998, Trumble’s book artfully deconstructs the smile “into more lines than are in the new map with the augmentation of the Indies,” as Malvolio is described in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. Trumble watches it arc through art, anthropology and advertising – “a fabulously versatile contortion,” he concludes, “capable of many meanings.” Its current ascendancy, he argues, has come about through advances in dental science – allowing the smile to loom larger, and toothier, than ever – coupled with the advent of photography and film. Both, Trumble writes, “brought about a fundamental change in the way people saw the human face, and how they expected it to look back at them.”

Whether it be Nicole Kidman’s or John Kerry’s, these days it’s most likely to come with a smile. The latter, we learn, is among 30% of the U.S. population who expose their canine teeth when they smile (67% form a toothless crescent shape); while women, unlike men, whose bodies secrete high levels of testosterone, are more likely to laugh. By book’s end, the reader has become familiar with the nasolabial fold (the curving lines which form between the cheeks and upper lip) and the inner-workings of the smile, whose principal puppet master is the cranial nerve number VII.

As one might expect from a scholar who has written wittily on Pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s obsession with the Australian wombat, Trumble saves much of his best material for the story’s marginalia. There are the early 18th century “gurning” competitions of York- shire (“The frightfull’st grinner/ Be the winner”) and the various cosmetic condiments that have accompanied the smile over the years, from the 18th century English vogue for wearing mouse-skin eyebrows, to the Japanese tooth-blackening practice of ohaguro. How the author manages to connect the 16th century European habit of dog turd-throwing, Dutch painting’s depiction of the chicken groper, and a potted history of the sheela-na-gig (the wanton witch engraved in medieval churches across England, Ireland and Wales) is part of the book’s but-I-digress charm.

But Trumble is principally a museum curator (formerly head of European art at the Art Gallery of South Australia, he is currently curator of painting and sculpture at the Yale Center of British Art in New Haven, Connecticut), and his book is strongest when it comes back to the picture. Through his eyes, he can make that most musty of matrons, the Mona Lisa, seem fresh again. Peeling back the sfumato of centuries of theory – from the femme fatale of European Romanticism to Freud’s assertion that her smile was that of Leonardo’s lost mother Caterina – he finds “an exceptionally subtle and sympathetic image of femininity.” She was, he says, simply the young wife of a Florentine merchant whose curling lips embody the essence of her husband’s name, Gioconda, meaning joyful.

Perhaps we see too much in a smile. For Trumble, there’s power in the mystery. Take Franz Hals’s The Laughing Cavalier, where all that really laughs is the Dutch military officer’s moustache. “A smile may stimulate us in certain superficial ways, eliciting a ready smile in response, for example, but it also penetrates the deep recesses of our subconscious mind,” Trumble writes. “What makes Hals’s portrait great is that it convinces us that something similar is taking place, even though we know at the same time that the source of stimulation is nothing more than paint on canvas.”

Like The Laughing Cavalier, Trumble’s book leaves you with a heightened awareness of the smile’s subliminal power. As you read this, buses around Sydney are advertising cider with a sepia photo of grave-faced frontiersmen: they saved their smiles for happy hour; while emails zip around cyberspace with the smiley emoticon of colon-dash-parenthesis. “The smile, meanwhile, is getting broader, wider, fiercer,” writes Trumble. And, as his book attests, more subversive than ever.